This week I took advantage in a gap in my eight-year-old son’s summer camp schedule to go hang out with an old childhood friend and his daughters. I brought along the recent Dungeons & Dragons Starter Set to run them through as a little campaign. We had two sessions scheduled, which I hoped would be enough to get a reasonable idea of whether these children could handle the hobby and, perhaps more importantly, if I was ready to use 5th edition Dungeons & Dragons as a game system with children as players.

Spoiler: It went pretty well.

Characters

Having five pre-generated characters with backgrounds and relationships to NPCs and ideals and goals was handy. The six-year-old girl’s dwarven cleric was related to the missing miners and was keen on rooting out some brigands in the town they were heading to. The nine-year-old girl’s halfling thief had bad blood with those same brigands and an aunt living in the town. The eight-year-old boy’s human fighter had a chip on his shoulder about his childhood home being overrun by zombies. The girls’ dad ran an elven wizard that was on a mission to re-consecrate an altar that had been co-opted by goblinoids (who turned out to be allied with the same brigands the girls had ties to). It also meant we didn’t have to blow our first session on making adventurers.

A trap that’s come up repeatedly over the years is character creation. Some games, including the most recent major revisions and clones of Dungeons & Dragons, have droves of enthusiasts that publicly obsess over the various methods and options of building new characters. That’s well and good, go have whatever fun you’re looking for. Personally I find more fun in actually playing the game than in making the characters. Simple character creation (and it gets no simpler than pre-generated characters) shortens the road between getting a group of people together and playing the game you got together for. That’s not so much praise for 5th edition D&D as an observation about a common speedbump at the beginning of many adventure campaigns.

The character sheets provided emphasize the character’s bonuses to rolls, not their numeric attribute score. I like this, as it almost never matters if you have a 17 dexterity or a 16 dexterity. What matters is that you get a +3 on dexterity-related activities. The +3 is big and visible across the table, the 16 is present for occasional reference. The cleric and wizard really would have benefited from a more useful presentation of available and prepared spells.

Rules

Advantage seems, with a short sample size of actual play experience, to be a good thing. The players were happy to have a second chance to roll a die even if they already knew the first result was good enough to succeed. We who play pen & paper RPGs like rolling dice. Contriving a situation that grants advantage to a roll lets us roll another die. That’s the kind of thing that appeals to the tactile lizard-brain part of fun that ought to be present in a game.

The new proficiency system made it almost alarmingly simple to remember what everybody ought to be adding to their rolls. If you’re proficient at something at first, second or third level (as far as we got) you get a +2 on top of whatever ability modifier you have. If you aren’t, you don’t.

The lack of a table of contents in the little sample rule book made a couple of references not-entirely convenient. What benefits do you get from surprising a foe? What are the rules for recovering from damage during a rest? It’s all in there somewhere, but I had to fudge a couple of rulings to keep things moving. Again, the advantage system served me well for DM-ignorance-related adjudication.

We never saw an actual roll with disadvantage during eight hours of play. I wonder if that is typical, or a quirk of our formative group dynamic.

The Adventure

None of the core concepts of the stock adventure’s premise were ground-breaking. There are some evil humanoids and criminals working for a shady puppet-master that’s trying to get at some ancient lost treasures of awesomeness. And a dragon. Nothing we haven’t heard before. Several of the bad-guys have explicit motivations that helped run them as the DM. What does the Nothic get out of working with the Redbrands? That informs how it interacts with the player characters.

The adventure starts by railroading the player characters towards a town that acts as the narrative hub of the story, dropping a couple of plot hooks along the way. Once in town, several notable NPCs had tasks they would like the players to take care of if possible. As mentioned before, the pre-generated characters tied in nicely with the setting. Everybody had reasons to be there. Just about every side-story the NPCs want to drag the party into had a character hook related. The thief wants revenge on the bandits. The lady at the assessor’s office wants the bandits dealt with and will pay handsomely. The archer wants to clear his home town of zombies and a dragon. The druid that knows where the super-secret hidden place is happens to hang out in that same town and another NPC gives the party directions to a treasure hidden there. A bunch of disjointed story threads tie together to provide the players with plenty of things to do and plenty of motivation to go do them.

Motivation is often lacking in published adventures. I suspect that’s tied into that character-building trap mentioned earlier. You want to play your special snowflake character. That special snowflake probably has no business existing anywhere, and certainly has no business helping the Rockseeker Brothers in their mining/archaeological endeavor. Or the good folk of Phandalin in general. Or the other player characters. Largely due to a reasonably-clever intertwining of pre-generated characters (that aren’t just a lump of stats and combat abilities) this adventure works quite well.

The challenges presented were simple enough for two total rookies and an eight-year-old with limited play experience to make just about all the decisions and get through it. That’s not entirely fair. Three little kids putting their heads together can come up with really good solutions to fantasy RPG problems. Don’t underestimate the cunning of two fourth graders and a devious little sister. They may take a little while to do their addition and subtraction, but their creativity is rock-solid. They explored, scouted, made good use of available resources, and circumvented threats with aplomb. At one point the cleric fell into a pit trap. A few minutes later they were using that same pit to their tactical advantage in a sword fight.

Over all we completed maybe two-fifths of the major content of the adventure. The players completed their initial assignment and took care of a major side-job, climbing rapidly from first to third character level in two sessions. There is still ample material to go through involving some overland travel, exploration of ruins, and hairy boss fights (some involving hairy bosses). I can reasonably expect these players to be fourth level well before finishing the main brunt of the story.

House Rules

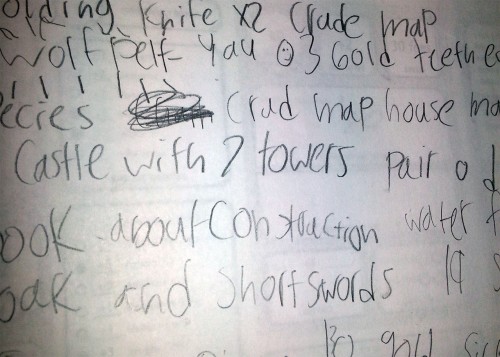

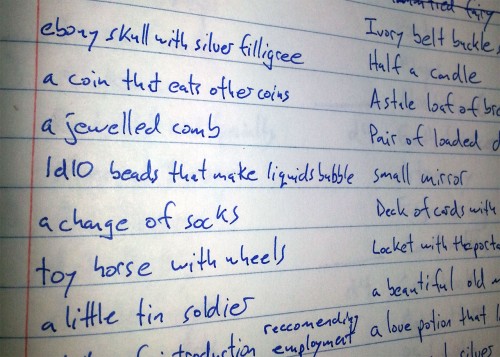

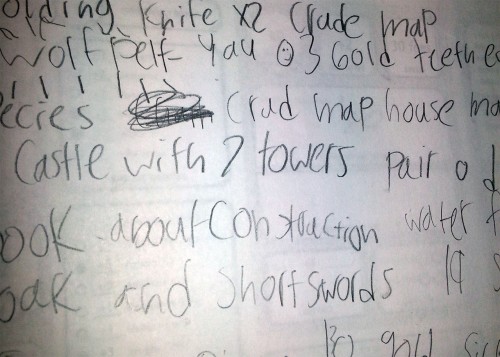

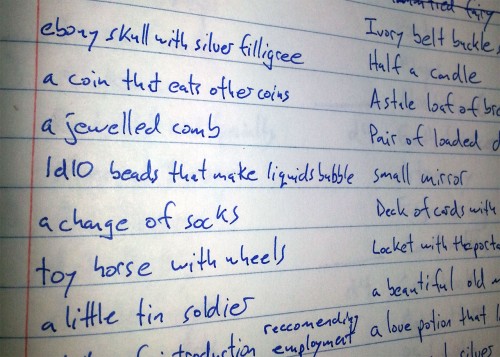

It just isn’t possible to play Dungeons & Dragons without some in-house strange rules coming up. In preparing for play I didn’t care for the way that very few creatures or antagonists had their inventories spelled out. I jotted down a modified “I search the body” table from the Vornheim city kit, as well as a modified “random book” table. Modified because I’m playing with children and some of that stuff is totally suitable for porn stars and not so much for grade-schoolers.

Upon looting a corpse (or captive), DM rolls 1d8. On a 1-7 a common item is found (a flask, 1d12 or 2d12 extra coins, that kind of thing). On an 8, something odd is found. DM rolls 1d12 and consults a list of thirty-odd items, counting down from the top of the list. Whatever the result is goes to the players and that line is crossed off. Interesting but not-terribly-valuable stuff goes at the top and is likely found earlier than interesting and increasingly-valuable stuff lower on the list. The little girls were somewhat disturbed to find a mummified fairy on a dead goblin, but later used it in negotiations with a hungry Nothic, so that worked out.

I may have bumped down the armor class of the goblins during the initial encounter. That wasn’t so much a house rule so much as I wanted to make sure their first-ever combat encounter wasn’t a total party kill because I have better dice luck than them. I was also inconsistent about whether groups of identical opponents all went on the same initiative count, based entirely off a read of the table as opposed to any hard-and-fast rule.

Conclusion

It’s refreshing to play a game that felt very old-school-nostalgia-fest with people that aren’t jaded by years of exposure to the narrative genre or the metagame tropes. During our second session we had a couple of problems with the two youngest kids running off to chase each other around the building, but I don’t think it’s entirely reasonable to expect young children to sit attentively for four hours straight.

Everybody should DM a gaggle of kids a time or two. Kids make for great murderhobos.